The second playtest was conducted at the end of spring quarter, with the final version of the game (minus some minor bug fixes). The test was conducted partially during the IGM Student Showcase, and partially online.

This test was intended to focus primarily on the quest aspect of the game, with a secondary focus on playability and confusion in general. However, we found that most people testing the game never used or cared about the quests in the game. This aspect made it rather difficult to test the quest system, but we got some good data about the game itself.

For the test, we made two versions of the game. The two versions differed only in how they handled quests. The control version emulated linear storytelling techniques by restricting the quest generation system severely so that it would only generate two linear quest paths. It also did not allow the generation of side quests. The test version generated quests based on character relationships and goals, and allowed the player to generate as many side quests and main quest lines as he wanted.

Whether a player got the test or control run was controlled by a random number. During the live playtest, we encountered some surprising problems with Flash’s random number generator: It would always generate 1 and not 0, which meant that all players initially got the control run. After a few test, we started manually switching the number instead of relying on the random number generator.

For the online test, we fixed this problem by using a different function to get a 1 or 0 out of a random number generated by Flash. Instead of rounding the random number (which is generated in the range 0-1) to the nearest integer, we multiplied it by two and rounded down. This worked much better, for some reason.

Most of the questions in the survey were multiple-choice questions that asked the players to rate their agreement or disagreement with a statement about the game. There was only one long-form question, and that was essentially the freeform comments section.

21 people playtested the game before these results were compiled. 8 people played the control run and 12 people played the test run. One person skipped the question about which run he played.

The questions were:

- I had fun playing the game.

- I would want to play this game again.

- I understood what I was doing and how I needed to do it.

- The game became less confusing as time went on.

- I felt like my actions and choices had a real, tangible effect.

- I felt like the game’s story was consistent with the game world.

- This game offered me [more / less / about as much] freedom as typical RPGs/story-based games.

- Comments? Questions? Bugs? Memorable experiences?

For the online test, since we could not observe the playtest, we added the following questions:

- Which “Test Number” did you have? (0 was test, 1 was control)

- Which of these things did you do in the game? (list of significant in-game events and actions)

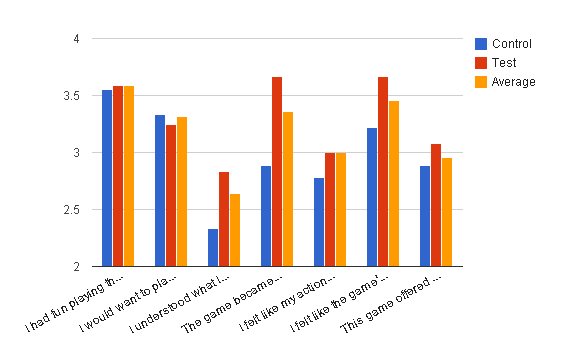

The results of the test were, as previously mentioned, quite inconclusive in terms of quest system analysis. (See figure below.) There was not very much variation at all between the test and control runs (see section 2.6.6 for a more complete analysis of this aspect of the playtest). In fact, at most half of the players actually completed a quest, and only 2-3 people completed half of the storyline (getting the bread OR the milk for mom). However, the playtest gave us some interesting data about the game in general.

|

Average answers for spring quarter playtest questions

|

Some of the highest ratings came from the question about world consistency: “I felt like the game’s story was consistent with the game world.” This reaction is very encouraging, since making an abstract story that nevertheless obeyed the rules of the game world was one of the main goals for this game.

For Micro Missions specifically, a little bit of confusion is not necessarily a bad thing: figuring out what the game and the world are about and how to navigate them is supposed to be a big part of the game. Micro Missions is modeled in part on the game flow of WarioWare, and just like WarioWare, the frantic, silly pace of the game should make creating and resolving confusion fun, not frustrating. But is the confusion in Micro Missions fun or frustrating? See below in Figure 4-6.

The data in the figure above implies that people did have fun while being confused. This graph shows all of the answers to the two questions, with understanding mapped against fun. The graph seems to show a weak positive correlation between understanding what’s going on and having fun. There were people who were confused but had lots of fun, and people who weren’t confused at all but didn’t have much fun.

A calculation of the correlation confirms this: the Pearson product moment correlation between the two statistics is 0.586. This is consistent with the theory that players need to understand some of what is going on to have fun, but are fine with being a little confused.

No comments:

Post a Comment